An AI-ready lab notebook for life science doesn’t need to be complex or expensive

How-to: An ELN+LIMS built in Notion + Airtable

Much has been said about the challenge of doing reproducible experimental biology and the need to capture minute details of each experiment. However, it’s proven really difficult to present wet lab researchers with tools that help them stay tidy and well documented. This post outlines the lab management system we use at Pioneer Labs—simple, cheap, and easy to modify—built entirely with generic software tools. If you're looking to adopt something similar, we walk through the system setup and share templates so you can copy or adapt it. If you're building tools for AI-assisted science, our corpus may be useful for you, and we share statistics and examples. Using and iterating on this sort of system sets us up for success, both in communicating within the team and taking advantage of LLM-based AI tools in the future.

We uses a mixture of Notion and Airtable for our Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) and Laboratory Inventory Management (LIMS) system, with the two halves glued together with syncing from Whalesync. It’s simple, it’s easy to modify, it has powerful automations, and it’s API accessible. It undergoes periodic tweaks and updates as our science evolves. We love it.

There have already been enormous upsides to having these systems function well.

The Pioneer team sometimes feels telepathic. People are generally quite aware of what other people are up to. There are automated weekly emails and slacks that go out summarizing the conclusions of experiments that have been finished recently. People are often asked to give other people’s work a read-through, both as a way to offer feedback and as a way to stay informed. A lot of things can happen async, including checking the details of someone else’s previous experiment without needing to talk to them.

We recently moved lab spaces and it was… easy?? Every sample in the fridge knows where it lives physically, and every experiment knows what samples it involves. It was easy to just write down where the boxes live in the new lab.

In addition, I expect there’s a third benefit that hasn’t been fully realized. As a result of having pretty much everything written down and organized, we’re in a good position to take advantage of AI systems to extract insight from our past experiments or better communicate results to one another and the world. Since opening 16 months ago, our wetlab team has grown to eight people and we have about 450k words worth of completed experiments. Can we leverage that corpus for further insight? If you’re an AI researcher who thinks so, let’s talk!

In total, this software costs ~$30/user/month. Here’s how we did it.

Jump ahead to

Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN)

If you haven’t seen ELeveNote’s excellent post on their Notion-based ELN, including how to clone and install their Notion template, read that now. We used ELeveNote’s Notion ELN template as a basis for our work. ELeveNote, thank you so much for sharing!!

In this system, each ‘experiment’ is a page in a Notion database of experiments. An experiment is a unit of work that has a well-defined goal and measure of success, and should take 1-3 weeks to complete. Experiment pages have a structured section containing consistent metadata like who is doing the experiment, what the status is, protocols used, and conclusions, as well as an unstructured page where people can keep their free-form daily lab notes, data analysis, and conclusions. Experiments can link out to Protocols and Materials that live in their respective additional Notion databases.

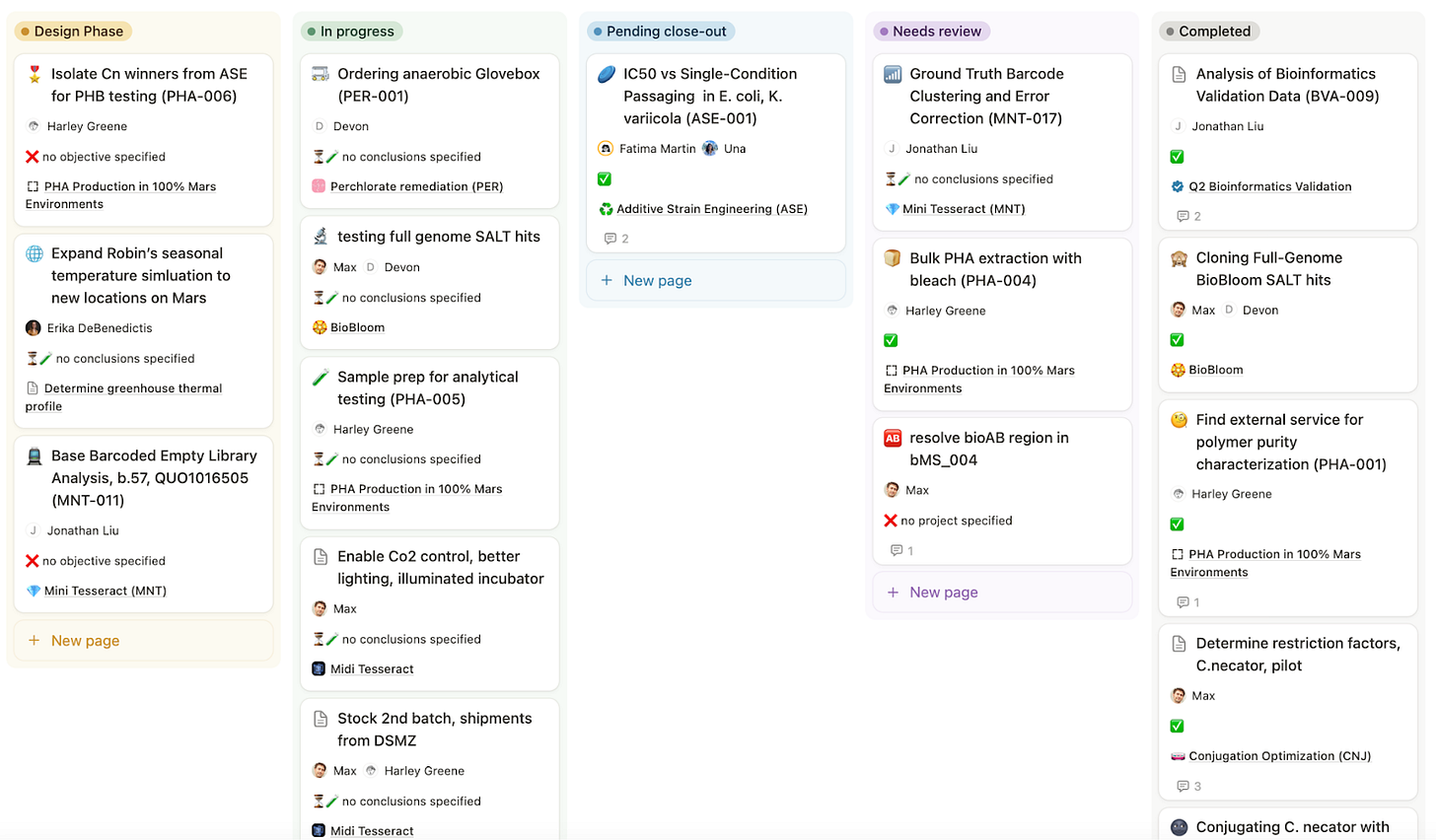

Each experiment has a lifecycle indicated by the ‘Status’ field. Here are some key options for the status field that tell the story of most experiments.

Future Experiment. This is the default tag, and we use this when you’ve created a page as a placeholder, knowing this sort of experiment is likely coming in the future.

Design Phase. Before picking up a pipette, we give ourselves some time to actually fill out the structured information at the top of each Experiment, write down the plan, and talk it through with other people before beginning.

In progress. If you’ve picked up a pipette, your experiment is in progress.

Pending close-out. If you no longer need to pipette anything, but you still are waiting on sequencing data, analysis, or need time to think through what happened and draw conclusions, your experiment is “pending close-out.”

In review. Once the original person who did the experiment is happy with it, they mark one or two other people to give it a read-through. The purpose of this is to simply get another set of eyes on it, look for anything ambiguous or missing, and make sure that six months from now we’re not sad and confused because we forgot to write something down. It also gives other people the opportunity to stay informed of results. Sometimes there’s a bit of back-and-forth in Notion comments to answer questions or debate conclusions.

Complete. Things are done, conclusions are written, and we’re generally confident that the paper trail is complete and understandable.

The conclusions field is enabled with a little AI writer. It’s only OK. The benefit is that it solves the blank page problem. When you go to finalize an experiment, you can click the magic AI wand to generate a draft conclusion, which will either be fine, or will be so bad that you’ll immediately fix it out of annoyance.

Modifications we made:

We added a Projects database. We wanted to create a place to outline the objectives of higher-level projects that contain many experiments before they’re complete. We created a project database that has a default template that has usual project charter elements- background, deliverables, risks, conclusions, etc. Experiments can link to the project they’re a part of.

Removed or don’t always use many original fields. Some fields like ‘raw data’ we keep around and people use them sometimes. But in practice it often seems easier to just upload raw data in-line.

Added many new status tags. We’ll talk about this down below in the “Drop it!” section. We created a number of new status tags that make it easy to choose not to continue a line of experimentation if it no longer serves us.

Adjusted the QC field. For the fields we do want to enforce, we adjusted the QC expression to check fields in the order they’re usually completed. When you first create an experiment it will remind you the “Measure of success” isn’t filled out, then later on it will remind you to fill out Conclusions, etc. By the time it’s sent for review the QC should give you a ✅. There is no hard enforcement of these fields, but the QC checker does a good job of reminding people what the expectation is for a complete experiment in a way that’s not too in-your-face.

Why not use Benchling? Word on the street is that Benchling will, allegedly, sell you their ELN for $1000/seat/year when you’re a new startup, then hold you up for $10,000/seat/year the minute they know you’ve raised a substantial amount of money. Additionally, you will never get your LIMS or ELN right on the first try. I wanted to choose something that invited people to modify it, and where the mechanism for making modifications is obvious. As soon as you’re a comfortable user of Notion or Airtable, you quickly become able to suggest “could we create a new database for X”, or “how about we have another column in this table?” It’s possible or likely that we will one day outgrow this system. For now it works very well, is less expensive than alternatives, allows us to iterate, and relies on generic software that is likely to have continued support and fairly stable price.

Automations

One major limitation of Notion is that its automations SUCK! We have a couple native Notion automations enabled to ping our #writeups slack channel when an experiment is listed as ‘In review’ or ‘Complete’. But unfortunately, Notion alone is incapable of doing any of the following totally reasonable and only slightly more complicated automations:

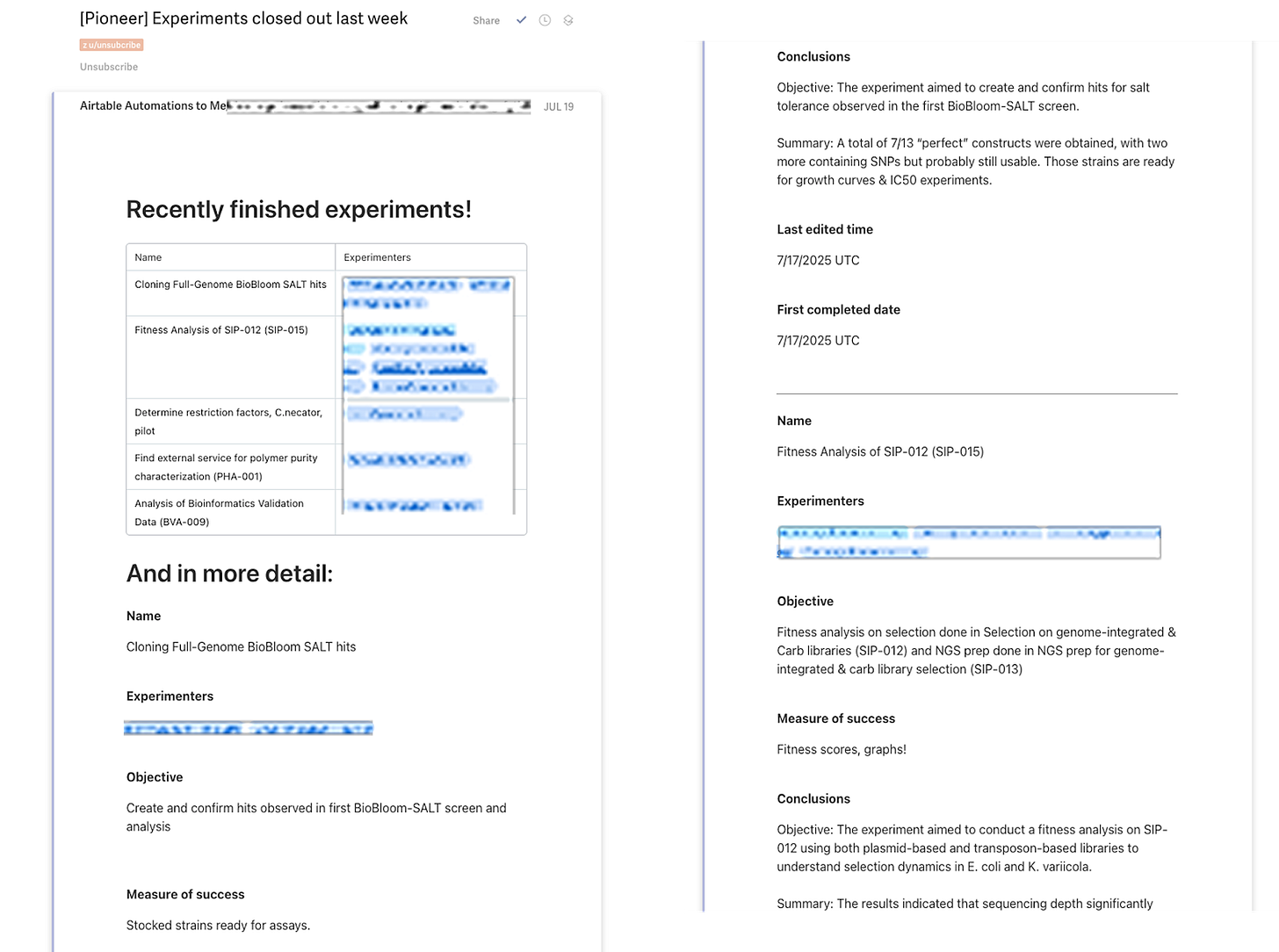

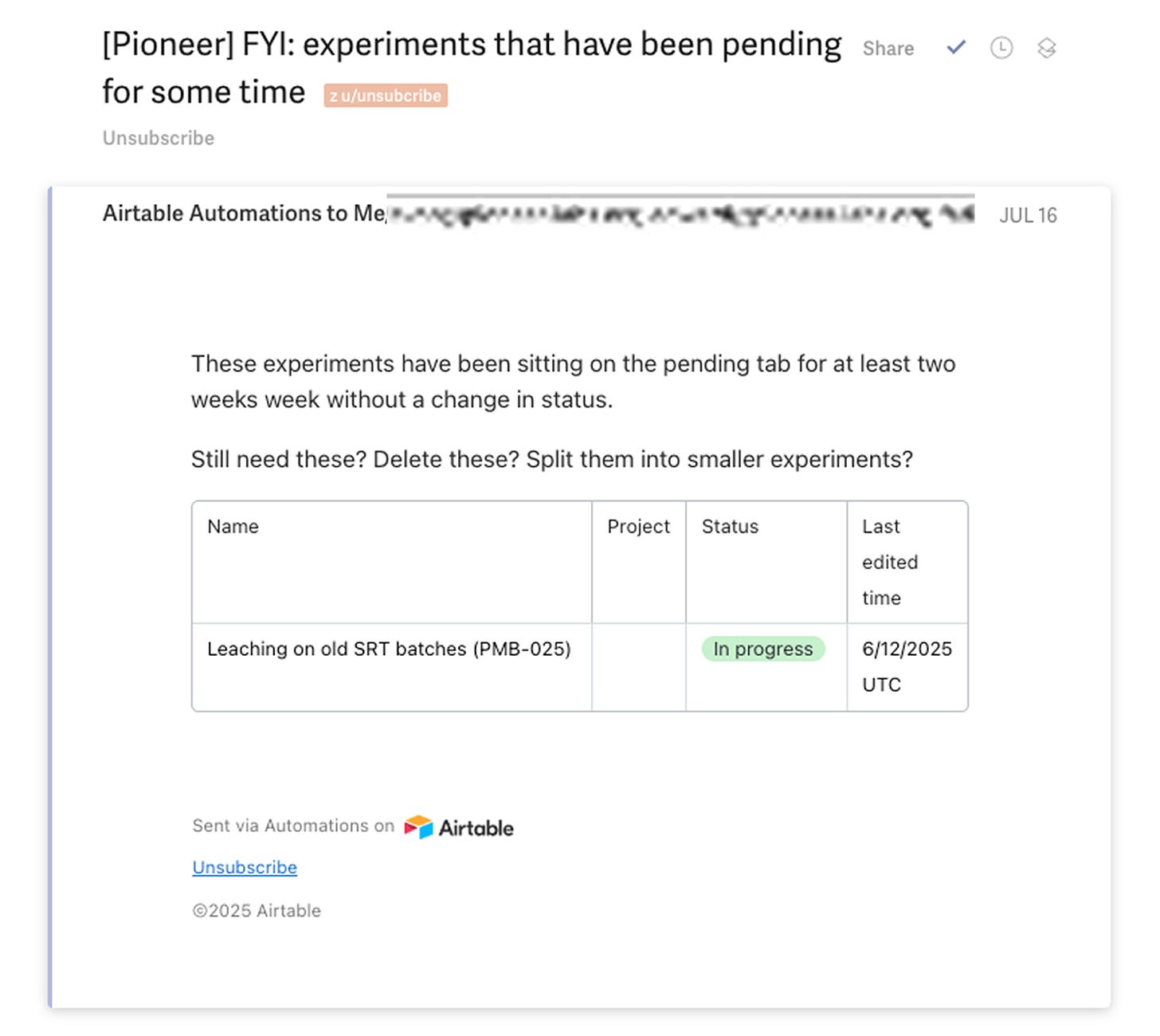

Every week, send out a summary email of all experiments that have been closed out and their conclusions

Remind people about pending reviews by sending a reminder email every Monday

Urge people not to leave things hanging/get stuck by pinging the group about experiments that haven’t changed status in 2+ weeks

Once an experiment has been ‘Complete’ for a week, change its tag to ‘Archived’ so it doesn’t show up on the dashboard.

To achieve these sorts of automations, we use a little third-party magic to take advantage of the much better automation features of airtable. We use Whalesync, one-way sync the contents of the Experiment database from Notion → Airtable. (For info on how to set up Whalesync and these automations, see below “How to use it”.) We use airtable automations for #1-#3 above, amongst others.

Limitations still exist. #4 still needs to be done by hand because it requires updating fields in Notion. It’s also somewhat annoying that I haven’t figured out a way for Airtable to send emails that contain direct links to Notion pages. This would require Notion to create a field that lists its own direct link. Seems like it should be possible, but I don’t know how, maybe I’m missing something obvious. If you know how to do this, please comment!

Drop it! Making it easy to STOP doing things

A result of the ELN is that everything that is happening in lab is written down, as well as a very large fraction of possible future experiments that people are considering. A disadvantage of having such a list is that it can easily feel like a TODO list. The implication is that everything that has been started or thought of must be finished. This is very bad! The ability to pivot quickly — discontinue working on experiments or projects that have been started when they no longer serve you — is more important than not losing track of things, especially in early stage research.

We put some thought into creating a system for forcing constant reevaluation of what we’re spending our time doing. Here’s what we came up with:

We created new status tags that articulate a couple different flavors of ‘choosing not to work on this right now.’ ‘Deprioritized’ means that we’re aware the experiment exists and might pick it back up at any moment, but it’s out-of-sight-and-mind for now, in favor of focusing on other things. ‘Icebox’ is a term borrowed from Arcadia, and refers to lines of inquiry that we think we’re unlikely to pick back up, sometimes because we’ve tried a different approach that worked better, or because we ran into a technical problem that makes it not worth the effort to continue.

Every few weeks, everything gets marked as Deprioritized. We do a ‘Priorities sync’ meeting every 4-6 weeks where we change the status of everything in ‘Design Phase’ or ‘In progress’ to ‘Deprioritized’. With everything ritualistically fully and completely dropped, we spend some real time talking about current results and set new goals. Often, we do this as a two-part meeting with a weekend in between so people can let the ideas marinade. Anything that’s mission critical for the new goals is reactivated. Everything else we leave behind.

Wet lab experiments take time. Continuing to do something must always be a choice.

Laboratory Inventory Management System (LIMS)

When I started my academic lab, I didn’t enforce the use of a standardized naming convention or a shared LIMS, and that was a big mistake that could never be recovered from. So when Pioneer began, we put an airtable-based LIMS system in place from before the lab opened. The label printer was one of the first items that got delivered to the lab. The first addgene plasmids we ever ordered were entered into the LIMS.

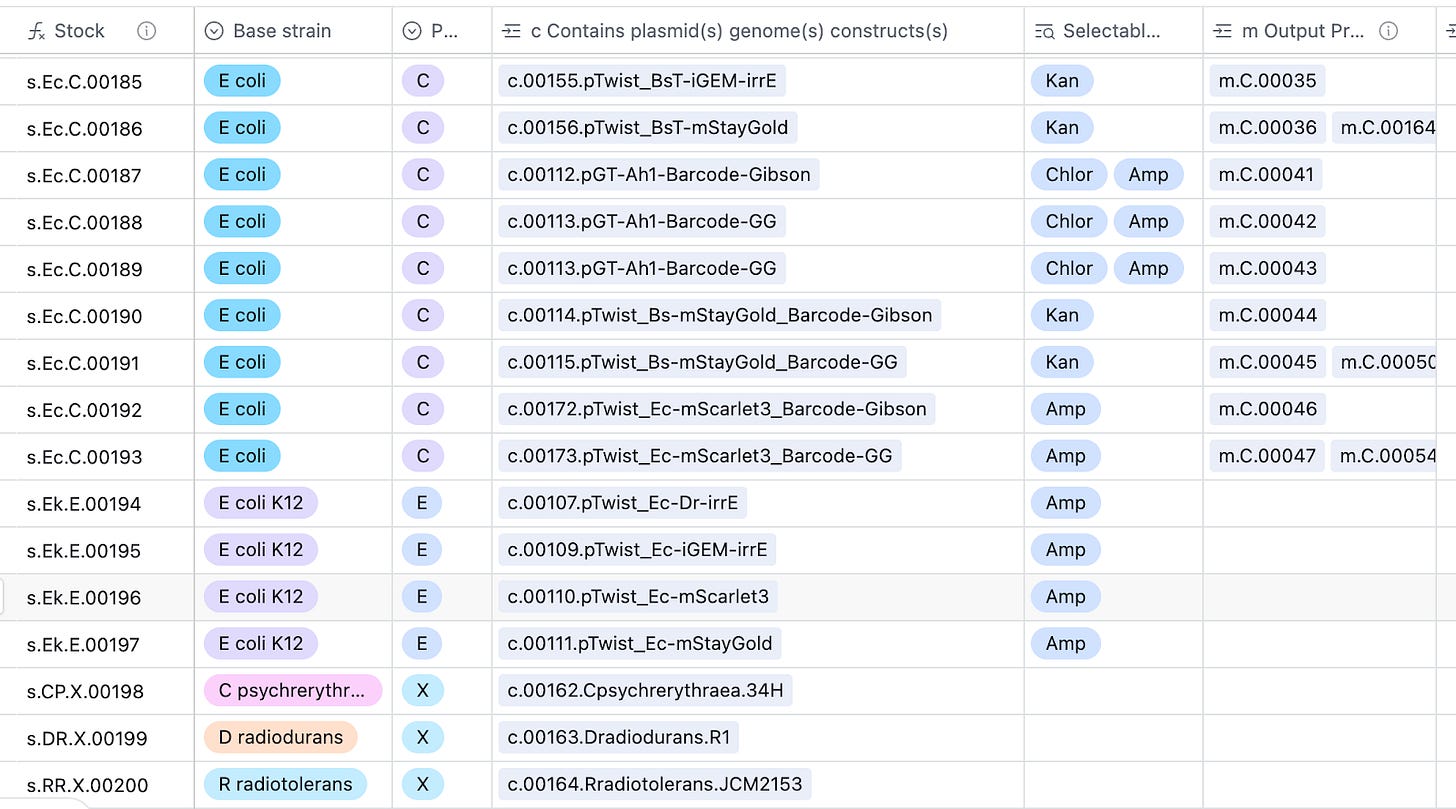

The LIMS is pretty simple and has naming conventions for four unique categories of things:

Stocks, s#####. A stock is any PHYSICAL TUBE of microbes, often stored as glycerol stock. They may be a mixed population, like a library or an evolved pool.

Primers and gblocks, p#####. Synthesized fragments of DNA including primers and gBlocks.

Preps, m#####. Preps of DNA, probably minipreps, maxipreps, and other sorts of genomic preps. Note that primers are NOT on this list.

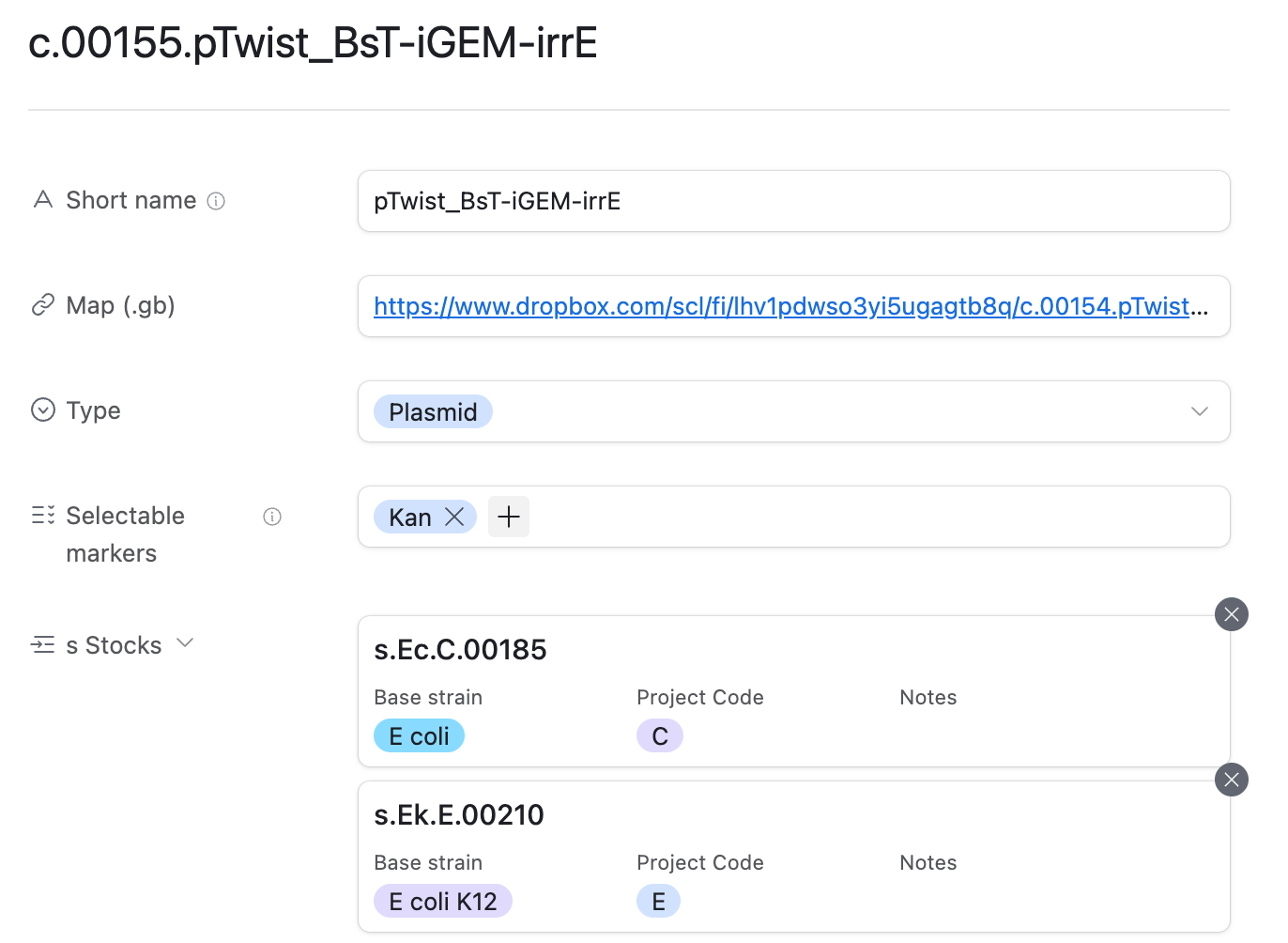

Constructs, c#####. Constructs are designs of DNA that have a well-defined sequence and corresponding map. A construct refers to a CONCEPT of a piece of DNA, NOT a physical sample of that piece of DNA. Most of our constructs are likely going to be plasmids.

The ground source of truth for the LIMS is airtable. It has a few fields that can be linked to one another, such as stocks can be linked to another parent-stock. Similarly, stocks are linked to the constructs they contain. Airtable formulas enable unique auto-numbering of entries, including a little bit of human-readability. For example, stocks of E. coli look like s.Ec.#####, whereas B. subtilis stocks are s.Bs.##### for convenience.

The LIMS began quite bare-bones, and over time we expanded it and made some changes.

Stocks now differentiate between ‘input’ and ‘output’ preps. Input preps were used in the creation of the stock, whereas output preps are derived from the stock. This replaced an earlier ‘linked preps’ field that did not distinguish the two.

Libraries, b#####. We added a new table for ‘libraries.’ We originally used constructs and stocks to track libraries with the simple addition of a marker in the plasmid map where the different library members might vary. We ended up wanting to track enough unique things about a specific cloned library - the estimate of how many variants it has, separate maps for the ‘backbone’ of the library versus of the ‘insert’, and more - that it made sense to break it out as its own type of LIMS object.

Plates, d#####. As our experiments became higher-throughput, we started getting bogged down in the details of how to represent plates-worth-of-samples in the LIMS. We went back and forth on simply repurposing the stocks table to handle 96-well plates, either by having a single stock correspond to a plate and have a further well index (e.g. s####.A3), or by having every well be entered as its own stock number. We ended up breaking plates into their own LIMS object that links to a standard format for plate map metadata that can be processed programmatically.

Everyone at Pioneer can edit the contents of the LIMS, but only two people can edit the schema itself. We’ve debated more LIMS changes than these, and only implement about half of the ideas that have come up to prevent bloat.

What it looks like

➡️ Here’s a few examples of experiment pages. ⬅️

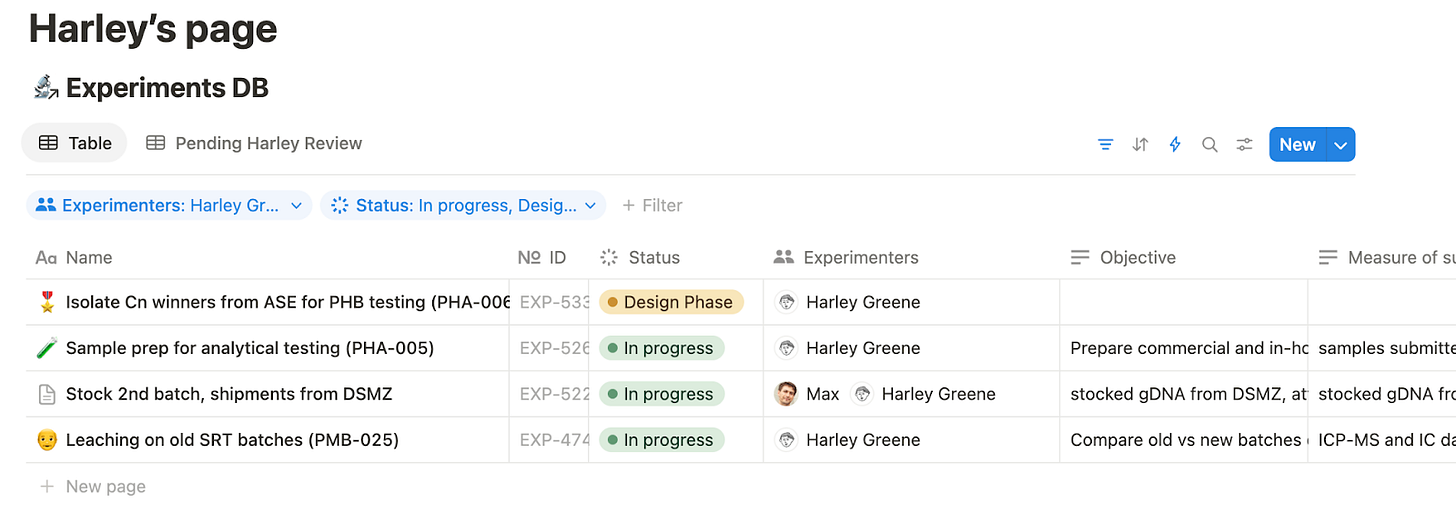

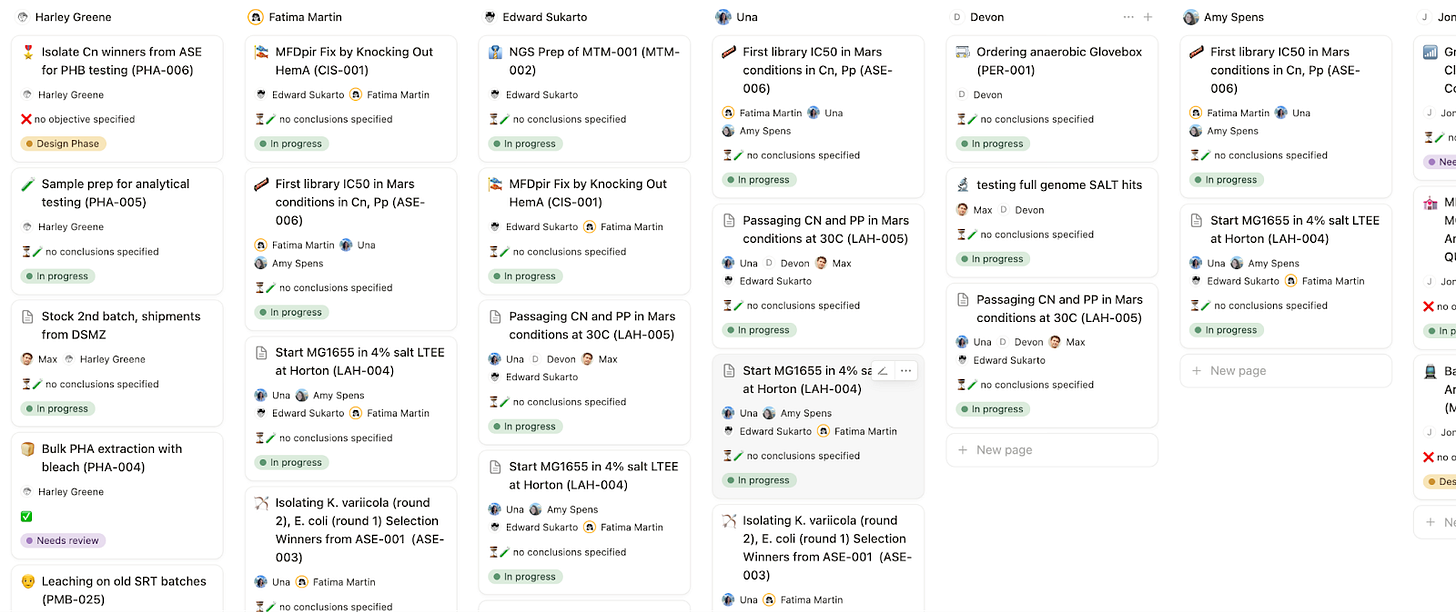

Using this system, each person has a dashboard listing the experiments they’re working on and feedback they’ve been asked to give.

We have a lab-wide dashboard for a birds-eye view of who’s doing what and status.

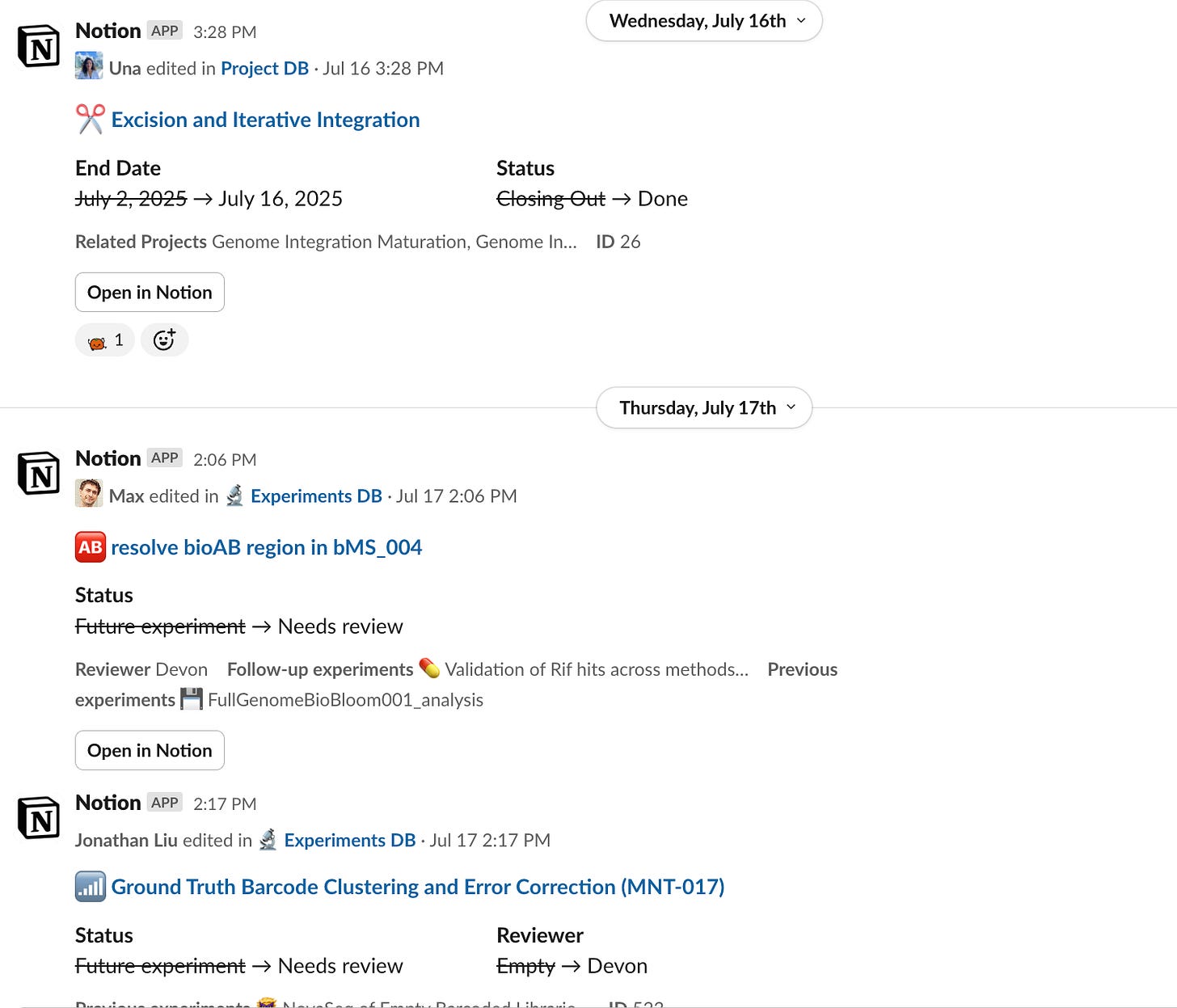

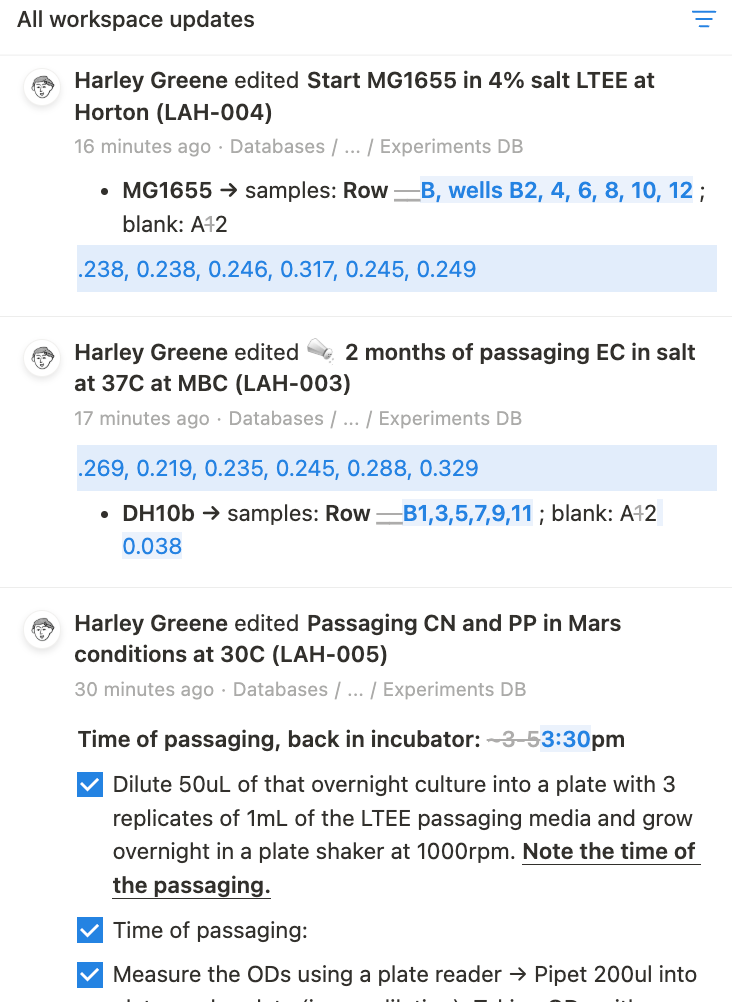

With a quick glance in the all-updates tab, you can get a granular sense of current goings-on.

You get awesome summary emails and reminders thanks to the Airtable emails.

And automations also help you keep things moving.

As well as slack integrations to make progress visible.

Meanwhile, the LIMS can be viewed and edited through airtable.

The construct table allows you to look up where a plasmid construct is stored in the fridge, as well as a direct link to its .gb plasmid map.

Things that don’t quite work… yet

Two-way syncing. When we first started, we actually used two-way syncing between Notion and Airtable with whalesync, and synced both the ELN and the LIMS. The benefit of doing this is that people were able to view and edit information in either tool, whichever one they were more comfortable with. The difficulty is that Whalesync is only so good, and it’s limited by the fact that Notion and Airtable aren’t exactly trying to make their APIs easy to work with. Every couple months, two-way syncing would break, and I’d have to go in there and figure out how to reauthenticate or tweak something to get it going again. The straw that broke the camel’s back was a catastrophic syncing failure where the LIMS had silently stopped syncing for about two weeks. Fortunately, with some careful inspection of the change history we didn’t lose anything, but I ended up turning off two-way syncs entirely. Now, LIMS lives in Airtable. ELN lives in Notion (with one-way-sync to airtable, ONLY for automations). The one-way syncs are totally stable and it’s been great. Two-way syncs are a trap, don’t do it!

Chrome add-on for one-click LIMS. Back in the day when we were two-way syncing LIMS data between Notion and Airtable, you could click on the linked LIMS object and view + edit data natively in a Notion lab notebook page. Once we stopped two-way-syncing, you had to copy the LIMS name and search for it in Airtable, adding a few clicks. Overall worth it for stability, but slightly annoying. We experimented with writing a simple chrome addon that simply displays all LIMS objects as clickable links in your browser. It is very simple: you enter a list of regex expressions for each type of LIMS object together with the airtable API key and table number it corresponds to, and the extension will automatically convert regex matches into links. The only issue is that it is just a tad laggy. Some people still use it. You can see a video here of the chrome extension in action. If you’d like to play with it or take a stab at editing please reach out, happy to share the code. With a bit more software engineering we could make this work well, and it’s quite a generally useful tool even beyond lab notebook IMO. (Why is this hard? The difficulty is that Notion pages aren’t HTML, they’re drawn in real time in a very complicated way, so doing this search-and-url-ify is not a simple matter of HTML injection, sadly.)

LIMS automatic analysis tool. This works but we don’t use it much. The idea is that because we have structured data, we have the opportunity to run standard analysis in anticipation that someone will need them, thus avoiding clicks. For example, when plasmidsaurus data gets added to the dropbox, we can parse the stock number out of the filename, look up the construct map it corresponds to, generate an alignment, and upload that alignment linked to the stock. We sort of implemented this, but still haven’t used it regularly. To do so, we created a new table called “Automatic Analysis" in Airtable and set up some scripts on AWS that have access to read/write keys to that table. One difficulty is that it’s quite hard to actuate AWS jobs based on new files in Dropbox. 🙄 Another issue is that I think we were just at such an early stage that the analysis we really need to do changed frequently enough that there aren’t super good opportunities to do default analysis all the time. I believe in automatic analysis and we’re now revisiting this concept!

Our ELN doesn’t exactly make sense for drylab? ELN works well for wet lab, but not so much for data analysis. Most computational analysis ends up happening in Jupyter notebooks on our AWS server, which makes it sort of weird to try to hook into our usual Notion notebooks experiment pages. For now, exploratory analysis gets done in Jupyter notebooks, and then just the conclusions get propagated to an ELN entry for visibility by the experimentalists. As our computational team expands, we’ll see how this evolves.

How to use it yourself

Build & customize your own

Together, this system costs $10/user/month for Notion and $24/user/month for Airtable. We also pay $120/month for whalesync (a single charge, not per-seat).

If you want to use all or part of this for yourself, here’s how:

If you want to use the ELN system, check out ELeveNote’s awesome blog post. It provides a Notion template and a walkthrough of how to install it. See the additional details about our updated QC function and expanded list of status tags.

To enable Airtable automations for the ELN, here’s details of how we set up Whalesync and airtable automations. You can find more background documentation on airtable automations.

We’ve prepared a template of our airtable LIMS that you can copy and modify. To use it, press Copy Base at the top. You can also read more about how to write formulas for LIMS object numbers.

Other questions? We’re super happy to answer questions or provide more materials. We benefited enormously from ELeveNote’s templates, so we’d like to pass it forward. Leave a comment below if you want more info or have a question or suggestion!

API access

Both Notion and Airtable have easy API access if you want to run things programmatically. I’ve only really found use cases for this with the LIMS, so here’s a quick example of how to use Airtable API:

Generate your API key through the Developer Hub button. There’s a guide here.

Grab the base and table ID directly from the airtable URL on the table you want to access. There’s a guide here.

You can use these keys with a python API. Here’s an example script that downloads and saves a table as a CSV.

from pyairtable import Api

api = Api("YOUR_AIRTABLE_API_KEY")

table = api.table("YOUR_AIRTABLE_BASE_ID", "YOUR_TABLE_ID")

records = table.all()

print(records)The ability to pull data from airtable and work with it offline is very useful. It allows you to do things like automatically pull the .gb file associated with a construct. In other instances (not the LIMS) I’ve used it to do things like network visualization of all the people in my personal airtable that tracks meetings.

Rule of thumb: For every API key you generate that allows write access, you probably should have ~10 keys that are read-only first. Programmatic write is a great way to screw over your system very quickly. Prototype everything with a read-only key first.

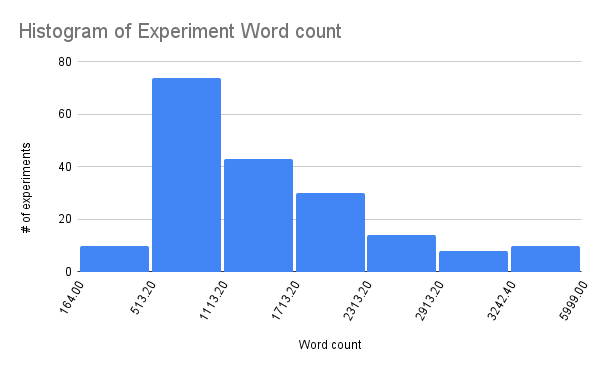

Do you do AI? Talk to us

For a sense of scale, Pioneer opened 16 months ago and currently has eight wet lab FTEs. Our ELN contains >300 completed experiments. The total corpus size is ~450k words: the median experiment is ~1200 words, with most experiments between 500-1000 words and a long tail of longer writeups. Our LIMS currently contains 1200 stocks, and 1600 other items.

Our ELN + LIMS system contains a mix of structured data and unstructured running lab notes. Between these two things, and the practice of reviewing experiments before they’re complete, we’re pretty sure we have close to everything written down. One would think that it would be possible to use AI to analyze this data and 1) surface what matters about our science to other researchers fast/better than normal manuscripts or even 2) design the best next experiment. If AI-insights-for-scientists is something you work on, we think our data might be useful to you. Please reach out! We are especially interested to hear from people who have already built such systems and are looking for test corpuses that can help mature their technology.

We’re hiring

There’s a lot of hiring going on at Pioneer and other orgs that are adjacent to me. Please check these out and pass these opportunities along to anyone who might be a good fit!

Automation Engineer at Pioneer Labs. Full-time in-person in Emeryville CA. Apply by August 10, 2025 for consideration. We have assays that are working and are limited by the number of hands in the lab, so it’s time to scale up! We’re looking for someone a proven track record of being scrappy and inventive with lab automation who enjoys working on a team and is excited to contribute to open source projects.

Senior Data Scientist at Pioneer Labs. Full-time in-person in Emeryville CA. Apply immediately, interviews in progress! The assays are working and we are making data faster than we can analyze it, please help.

Residency Program Director at The Astera Institute. Full-time in-person in Emeryville CA. Be my boss! 😛 We’re looking for someone who excels at operations and out-of-the box thinking who can help me and other members of the science residency program navigate the ambiguous world of running projects that don’t fit cleanly into VC-backed startups or academia.

Scientist at The Align Foundation. Full-time in-person in Washington DC. Apply by July 31, 2025 for consideration. Be embedded with Align’s amazing collaborator David Ross at NIST and work on expanding GROQ-Seq as a public data platform, especially to conduct scalable measurements of protein expression, or protein function in new microbes. You can read about the latest technical status of the GROQ-Seq project for background.

Research Associate at The Align Foundation. Full-time in-person in Boston, MA. Apply by July 31, 2025 for consideration. Be embedded at the DAMP Lab in Boston, one of Align’s collaborating data generation facilities. We’re looking for someone with some automation experience to rock and roll running GROQ-Seq data collection for a wide variety of transcription factor engineering projects.

Conclusion

Thanks to the team at Pioneer for the incredible work and the dedication to good communication with one another 🫶. You can sign up to read scientific updates through Pioneer’s substack. For more essays on automation and biological engineering, subscribe to my substack below.

"Once an experiment has been ‘Complete’ for a week, change its tag to ‘Archived’ so it doesn’t show up on the dashboard."

Notion certainly has many limitations (and I say that as a diehard Notion 'stan) but I don't see how this is one of them. Just create a view of your database that has an "advanced" filter rule of "(status is not complete) OR (status is complete AND last edited time < 1 week ago).

Thanks for a detailed and inspiring write-up. I'm constantly trying to improve the organization of my lab notes and your approach brings a refreshing perspective.

I've got a few practical questions:

1. Do you have certain structure/guidelines to the free-form part of the Experiment page where people keep their daily notes? I find that enforcing a certain structure helps with readability and lowers chances of errors but is quite time consuming to do, especially when developing new assays. I find that people in many cases end up leaving out a lot of information (e.g., final concentrations because it takes time to compute them) or perform smaller scale experiments even though they could run many more conditions in parallel if they just planned better. I've experimented with ChatGPT o3-generated protocols based on the input materials and goals of an experiment, and that works ok but still needs a few iterations and manual fixes to work properly.

2. How do you decide that a new Experiment page needs to be started? Personally, I find that I often need to optimize my assay quite a bit before it works well, and more often than not it involves testing/optimizing smaller bits of the originally planned experiment. I end up starting a new page for these side quests, but then it becomes disorganized quickly. Perhaps a Project page is a sufficient solution. Or just accepting that experiments branch out organically and there should be no expectation of a perfect order.

3. How do you keep your output materials organized in a box? I understand that each one gets a label, but the label is not self-explanatory. Does that mean people in the lab must constantly loop up materials in the database? Do you have laptops just sitting in the lab for that purpose? We use tablets in our lab but I find them only good for viewing, not adding new entries, and people don't want to bring their laptops to a wet lab due to a possible contamination. Also, entering every single tube with the outputs of an experiment into a database and printing labels seems somewhat tedious (in spite of how useful it is!) – I wonder how easy it was for your researchers to adopt to this new habit.