Erika's quick-start guide to research nonprofits

You do NOT need permission from a university to do research (!!)

Introduction

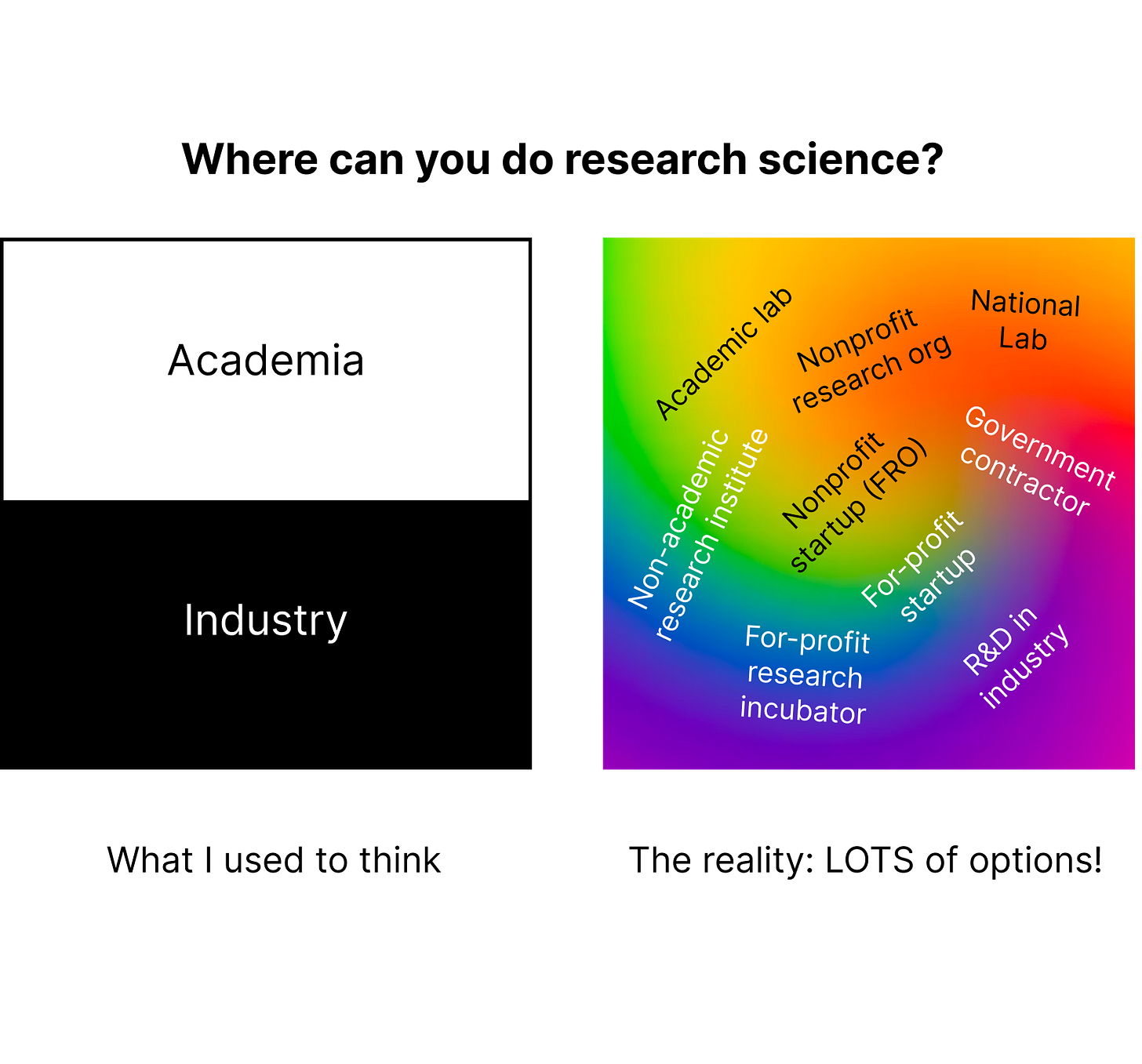

When I came to the end of my PhD, I was offered a black and white choice: academia or industry. It’s a false dichotomy. The reality is that there are many different shapes and sizes of scientific projects, and they don’t all fit into the academia OR the industry box. There’s a burgeoning world out there of people creating a richer ecosystem of niches in which science can thrive.

There are many research projects that are not supported by the current ecosystem. Indeed, the science ecosystem prematurely converged on a relatively small number of mechanisms for funding, organizing, and incentivizing research. Some mainstays of scientific research today include: use of peer review to evaluate proposals/outputs and allocation of small grants to professors at a university for the purpose of supporting their trainees.

Want to lead a team of experienced mid-career folks rather than trainees? Tough — if they’re not willing to have a postdoc salary you’re pretty much out of luck!

Would the scientific ecosystem be improved by a new benchmark or standard that you know how to develop? If it doesn’t make a profit or generate high-impact peer-reviewed publications, no-can-do.

Fortunately, philanthropists are increasingly partnering with independent research non-profits to more fully explore the space of possible institutional structures. Research non-profits can be designed to fit the given scientific goal, rather than the other way around: designing a project to fit in the ‘academia’ or ‘industry’ box.

This post is a brief guide to starting a nonprofit research organization outside of academia that is philanthropically funded. There is nothing magic about the resources offered by academia. The mechanics of setting up a nonprofit research organization are very straightforward. Philanthropic fundraising can be challenging, but IMO it’s a lot easier than writing an R01.

There is nothing magic about the resources offered by academia.

Disclaimer: I’m not a lawyer and this isn’t designed to be comprehensive. These are my hot takes + first person experience from starting Align Bio. I’ve raised $10M+ in philanthropic funding outside of academia for Align. I also run an academic lab at the Francis Crick Institute.

How to get started - write a “two-pager”

To get started, usually you write a ‘two-pager’ about what you want to do. Start emailing it around to see who might be interested in helping you. Help can take many forms: feedback on your pitch, ongoing mentorship and advice, and most importantly warm introductions to other people and to potential funders.

Is there a format for your two-pager? Nope! Unlike writing an academic grant, the two-pager is just a short PDF that you can attach to an email that gives the person you’re talking to additional background about what you’re doing and a way to remember you. (This type of document is called different things in different disciplines, when you’re lobbying on the Hill, it’s called a “leave-behind,” for academic funders it’s sort of equivalent to a Letter Of Intent, or LOI.)

Two-pagers don’t literally need to be two-pages. I like to structure them in sort of a scale-invariant way. A two-pager is a document that makes sense if you read just the first paragraph, the first page, the first two pages, the first four pages, or the whole thing. Make sure there’s a good diagram on the first page. I usually include the ‘details’ in a ‘technical appendix’ on pages 3+ for folks who actually are curious. Here’s an example ‘two-pager’ that I used to fundraise for Align’s Open Dataset Initiative.

How to get connected

The social network of people who do science and people who do philanthropy is very densely connected. You are probably a lot fewer than six degrees separated from your future funder!

Start by reaching out to anyone and everyone who seems like they might be able to point you in the right direction. A good place to start is by looking at the research nonprofit founder community, especially people who are already executing on projects with similar themes to what you want to do.

Here’s a list of organizations that fall in-between “academia” and “industry”. All of these organizations are experiments in new institutional models for doing scientific projects. Check out their websites and find people to email. If you're squeamish about cold-emailing, get over it, and/or use linkedin to engineer warm intros for yourself to people at these organizations.

Convergent. Convergent specializes in the Focused Research Organization model for large, time-bound research projects.

SpecTech. Another nonprofit aiming to run ARPA-like research programs.

Align Bio. This is my nonprofit! We give grants and run programs focused on the themes of automation, data, and reproducibility in life science.

Future House. An independent nonprofit research institute focused on building an AI scientist.

Arc Institute. A independent nonprofit research institute focused on biomedicine.

Arcadia. A for-profit, “run-by-scientists” incubator, technically grounded in working with microbes.

Homeworld Collective. A nonprofit running experiments in new funding structures for climate science.

And others! See also arbesman.net/overedge/

Send an email with your two-pager attached and ask for a zoom call. Every time you talk to a new person make sure to ask them who else they think you should talk to, and whether or not they would be able to give a warm intro. Use these calls as an opportunity to iterate on your pitch. We’re all very friendly, and can help route you in the right direction.

In addition to asking people to route you organically, you can also do your own research and identify philanthropists you want to talk to. You can also check out the list of people who have signed The Giving Pledge (a commitment billionaires sign to give away their wealth during their lifetime) and identify people who have a history of being interested in relevant causes. Again, you can try to use linkedin to find a path between you and people you want to talk to. In my experience this strategy is less fruitful than allowing people to point you in the right direction organically.

How to fundraise

You need to be shameless about asking for intros and articulate about what you’re trying to do. You need to talk to a lot of people and listen very carefully to what they care about. It’s a similar grind to raising VC money, but with a different target audience.

Philanthropy is about relationships, not paperwork

You will need to fundraise for longer than you think and talk to way more people than you expect. Finding the right philanthropist is about talking to a lot of people, listening very carefully to what they care about, and describing what the project you want to do would look like in partnership with them. There are a lot of good reasons to do science! Listen very carefully and tailor your pitch to suit the taste of the person you’re talking to. These are cool people who care about science and want to help!

If they’re serious, often they will ask you to send them something more detailed than your ‘two-pager’. Some philanthropists may have formats for the proposal at this point and/or a structured review process, others may just show your two-pager as-is to technical experts they trust for a second opinion. Usually the first indication that a philanthropist is going to fund you is they start coaching you about how to get through their due diligence process. Other times you may not have a ton of indication of what's going on, you may pitch to someone and then receive money months later with no contact in between. If you want to know what to expect you can ask around to other grantees to learn what’s typical for a particular philanthropist.

All together, you probably aren’t going to write anywhere near as much paperwork to get funded as you would for an equivalently-sized academic grant. Your goal is to convince just ONE specific person, not a panel of anonymous reviewers, and the task is understanding them and appealing to them.

Keep in mind that there is a lot of science philanthropy. In the US alone, philanthropists fund $30B of research/year. High net-worth individuals sometimes give money directly, other times they may donate through their own foundation, or through foundations that route donations from many donors. You may not end up talking directly to “the philanthropist,” but rather to someone running their philanthropic foundation who they trust to vet philanthropic opportunities for them.

But how does philanthropy work??? What do they get out of it?

When I explain that my research projects are philanthropically funded, people often ask, “but what does the philanthropist get out of it?”

It used to be that rich people would spend their money to buy some fancy purple cloth to make a fabulous cape, or some spices to make hot chocolate. We now have wealthy people who are so rich that the only thing worth buying is paying someone $100M to send a spacecraft to the nearest star. Science is the new luxury good. Much like commissioning art, science philanthropy gives philanthropists the opportunity to make research projects happen that might not be funded any other way. It also gives them a unique lever to change the world by accelerating basic research on issues they care about like climate, health, space, etc.

Science is a luxury good that appeals to people who are already financially successful in traditional ways and still want to change the world. Philanthropists are themselves often really interesting, talented, cool people.

This is very different to venture capital money. In venture, the person giving you money has a legal responsibility to make a return on investment. They literally CAN’T give you money if they don’t in good faith think you are a good investment (they could be sued). Philanthropy is uniquely capable of funding certain types of projects. That’s part of why it’s special and philanthropists like to do it.

The entire point is that they don’t need to get anything material out of it.

What is the ongoing relationship with the philanthropist?

Once you find someone who wants to fund you there are two different ways they can give you money: gifts, and grants.

A gift is a no-strings-attached donation. They give you the money, and it’s up to you to spend it. A gift just requires that you give them details to wire money to your nonprofit’s bank account (see next section).

A grant is slightly more hands-on. Grant payments are sometimes traunched on meeting milestones, much like DARPA grants. (“Traunched” means broken into different “chunks” of funding, so you might traunch a $2M grant into four $500k chunks, each successively unlocked by milestones.) A grant will usually have a grant agreement that is signed between the two parties outlining what the payment schedule and milestones are. Once signed, you also give them bank details (see next section).

Whether it’s a gift or a grant, different philanthropists may have different expectations about how much you will interact with them. The philanthropists I’ve worked with seem to be quite hands-off. If I have a question, want an intro, or need advice I can always reach out and they’re super helpful, but otherwise they don’t seem to expect a ton of contact. Your mileage may vary.

How to get a bank account

Congratulations, you found someone to give you money! Next step: what bank details do you give them? Literally, where do you PUT the money?

(In this quickstart, I’m going to assume that you have a research program idea that doesn’t fit into academia OR industry OR one of the existing nonprofit research science institutions listed in the “getting connected” section. Conversely, if your idea does fit, it’s well worth just using an existing institution and not reinventing the wheel. For example, if you want to do a project that fits in the “$50M over 5 years” bucket, it’s very worth talking to Convergent.)

Easy mode: get a fiscal sponsor

All you really need to get started is a bank account and someone to file the tax paperwork for your nonprofit. Fortunately, there’s a name for a nonprofit that does exactly this for other nonprofits: a fiscal sponsor!

Haven’t heard of a ‘fiscal sponsor’ before? Sure you have! Universities are fiscal sponsors for all the academic labs within them. Rather than have every separate academic lab spin up its own incorporated nonprofit, file its own taxes, and have its own bank account, the university is just a single umbrella nonprofit that does tax paperwork and accounting for all the labs within it. Fiscal sponsors act just like universities: you can come to them with gift or grant money, open an account, and they’ll take care of the paperwork on the back end for you.

Like Universities, fiscal sponsors usually charge ‘overhead’ to pay for the administrative services they offer. Unlike universities, fiscal sponsors charge WAY less. Universities often have overhead rates of 50% or even 100%, while fiscal sponsors are more like 10%.

You should shop around for a fiscal sponsor who is experienced with sponsoring projects of the type/scale/needs that you have. I’ve worked with The Federation of American Scientists. Another couple to check out are Rethink Charity, PFF, and Tides.

Every fiscal sponsor is a little bit different. Some, like Rethink, require that you submit a budget upfront that needs to be approved by their board. Once approved, you have very little leeway in updating the budget (i.e., you need to spend only on the things that you said you would spend on). Others, like PPF, are more flexible but require that you submit documentation for each distribution that you request and get their approval on contracts. The fiscal sponsor will take care of the compliance and filing taxes. Your organization will be responsible for signing all contracts, hiring employees, managing payroll, etc (see “how to spend money” section below).

There’s lots of different fiscal sponsors and they’ll all be set up for different sorts of projects. They’ll often have an ‘application’ on their website that you can fill out to chat with them. If they’re not the right fit they can usually point you in the right direction.

Slightly more sophisticated: set up your own nonprofit

If you want something more bespoke you can go straight to incorporating a dedicated nonprofit.

How to do this? You can file the paperwork on your own if you want, but most people I know just email Kitty Bickford (support[at]taxexempt501c3.com) and have her do it for you. She’ll send you a brief questionnaire and help you work through issues like “but the name I wanted isn’t available in the state I wanted”. She’ll do all the paperwork for you. It costs about $1,600 to set up a non-profit through Kitty, total.

In order to create a new nonprofit you need just a couple things including:

A name

At least three board members (who are not related to one another). More suggestions for picking board members here.

A mission statement. The board members will be legally obligated to uphold the mission of the nonprofit. You can create a mission statement by telling Kitty what sorts of activities your nonprofit will do, and she will help you translate it into standard nonprofit lingo.

If you know the name and board members you can file paperwork essentially immediately. What takes longer is getting your ‘determination letter’ from the IRS. This is the letter that gives an official “nonprofit” stamp on your organization, and thus be eligible to receive nonprofit donations. If left to their own devices, it takes 7-10 months for the IRS to get around to issuing your determination letter. However, once you have money actually lined up you can ask to expedite this timeline, which can reduce the wait to ~2 months or less. It usually helps to file the expedition request and then call the IRS every few weeks until they send you the letter.

You will also need to file your Charitable Registration in each state where you are receiving funds before receiving funds. Kitty can help you do this, or companies like Harbor Compliance or Labyrinth offer services to manage your Charitable Registration and Annual Renewals for you.

Once set up, your new shiny nonprofit will need to hold a board meeting at least once a year, and will need to file taxes. Kitty will provide you with how-to documents for everything from taking minutes at the Board meeting to recognizing scam snail mail that your nonprofit will receive. Kitty can file taxes for you yearly, expect it to cost $2-3k/year.

As a person extremely allergic to paperwork of all forms, I absolutely wanted to skip this entire process and go for the fiscal sponsor route! Indeed, what would ever possess someone to set up a dedicated nonprofit?! The answer is that you may eventually outgrow your fiscal sponsor and need a dedicated nonprofit. Because the fiscal sponsor hosts other projects, they sometimes can’t do things like, say, enter into exclusive contracts with other corporations. You also may want to isolate legal liability to just your project. Fiscal sponsors (understandably) tend to be pretty conservative about the sorts of contracts they sign.

How to spend money

Congrats - you now have money in the bank! Now how do you spend it?

This is where we get into “ops”. As a person coming from academia, I didn’t even know what “ops” is. Ops is short for operations, and basically refers to all the nitty-gritty stuff that needs to get done to make an organization go, like managing the bank account, filing taxes, paying people, making sure the people have healthcare, and processing reimbursements.

Ops is a lot of work, but fortunately if you have a small nonprofit you can outsource all of your ops pretty easily. If you have a fiscal sponsor, they may take care of some of this for you.

Here’s a basic set of outsourcing I’d recommend:

Mission First Ops. They’re excellent. They will take care of many of the mechanics of making a functional nonprofit, and also provide good support, advice, and connections. They are very reasonably priced and vastly less expensive than hiring an ops person. Mission First has also worked with quite a few of the recent nonprofits-for-science, so they know what’s up. As a sampling of the things Mission First will do for you:

Mission First will register in every state where you employ someone (for tax and withholding purposes).

If you are not already using Kitty Bickford to file your yearly taxes, Mission First can connect you to an accountant. Expect a tax accountant to cost $2-$3k/year.

Mission First can connect you to NFP, a broker who can provide you with business insurance. Expect business insurance to cost $2.5-$4k/year.

If you want to get healthcare for employees, Mission First will connect you to a benefits consultant who can help you find plans/coverage options.

Mission First can refer you to a lawyer who you can keep on hand to draft contracts, review contracts, ask compliance questions, etc.

Quickbooks. Obviously. We use this for accounting, it makes it very easy to file taxes and clicks in effortlessly with…

Ramp. Ramp is a really slick tool to use for giving people corporate credit cards and handling receipts. You can forward receipts via email to a ramp email address, and they will get automatically attached to the corresponding credit card charges. They also have an app where you can just take a picture of the receipt. It all hooks into quickbooks so that it’s easy for Mission First to file your taxes.

Gusto. We use them for payroll, again through Mission First.

Velocity Global. When you are first getting set up, it can be difficult to get all of the benefits in place when you have only one or two employees and no company history. Velocity Global is a professional employer organization (PEO) that can hire your employees for you. They can also help you hire people internationally. My nonprofit (Align) is unusual because we have employees in three different countries, despite only having five employees! Velocity Global is how we employ people outside of the US. If you want to make an offer to someone international, just give Velocity Global the heads up, and a few weeks later they will have spun up all the legal stuff necessary to employ someone internationally with benefits. Note that employing someone internationally does add a bit to the cost.

Outsourcing ops tends to be a great idea for small organizations. If your organization grows to the size or complexity that you feel the need to hire a dedicated lab manager or HR person, it’s probably time to start doing your own ops in-house.

How to hire people

Now that everything’s set up, it’s time to work! In order to get things done, you need to be able to hire people, either part-time as contractors or full-time as employees.

Let’s start with contractors. Setting up a consulting contract is a nice way to formally engage someone to do a small amount of work for you. To do this, you want to write a statement of work (here’s an example statement of work), which outlines the scope of what this person will be doing. Sync with your lawyer to generate a contract that incorporates this statement of work and how much they’ll be paid. Both of you sign the contract. When they’ve done their work they can submit an invoice (here’s an example invoice template), which you can then use to pay them through gusto.

If you want to hire someone, you begin by writing a job description. Here’s an example of a job description. To get the word out, make a PDF of the job description, put it on your website, send it to your friends, post it on linkedin, post on twitter, and hit up relevant mailing lists/communities. (In my experience, posting on linkedin is valuable, but using their job advertisement feature seems to mostly generate spam applications.)

Nonprofits are required to justify the salaries they pay employees by benchmarking against equivalent roles in other organizations. To pull salary data, you need to go to a website like Option Impact to find ‘comps,’ or comparable salary data. (Note that getting access to salary data through Option Impact is pretty expensive, but there are cheaper options like glassdoor.) So for example, if you’re looking to hire a Project Manager, you can look for project managers in your same technical field in the geographic area you’re looking at, and filter by organizations that are roughly the same size. This will give you a sense for roughly what you should be paying people. If you plan to use industry-esque salaries in biotech, Petri has a great reference for biotech compensation.

If you discover you need to hire someone who has very specific expertise and comes from an especially well-compensated discipline (like, say, machine learning), you can ask to get a copy of their previous contract and/or find other comparable salary information for their more specific role, which will allow you to justify a higher salary.

Keep in mind that employees cost you more than you pay them. A good rule of thumb is that benefits for an employee cost about 30-35% of their base salary.

Once you agree on a salary, a start date, and a job description you’re all set to hire the person. You will also want to keep notes from interviewing candidates and checking references on file.

How to get lab space

Align doesn’t do bench work at all (we do cloud science 😛), but many people who do research may need access to facilities. In general, it seems like the usual rent-a-bench ecosystem for startups is pretty friendly to research nonprofits. In the Bay Area you can rent a bench with access to standard shared wet lab equipment for about $2k/bench/month at places like MBC Biolabs, BADASS Labs, Bakar Hall, or numerous other incubator spaces. These places create a very, very easy way to get started. They are completely turnkey.

If you grow beyond 10 or 20 bench scientists, it will become more economical to lease your own dedicated lab space. To get a sense of order of magnitude, the price for built-out lab space in the Bay area is about $5/sqft/month. 5,000 sqft is about the right amount of space for ~10 people. So if you have a research nonprofit with 20 scientists, you may be paying (ballpark) about $0.5M/year to lease space.

How to manage IP and spinouts

IP is pretty simple and similar to the University model. The University/your nonprofit is a nonprofit entity that holds an IP portfolio generated by employees. When a postdoc/an employee of your nonprofit wants to start a company, they license the IP from the nonprofit.

At a university, IP licensing decisions are made by a bunch of patent attorneys who are trying (and pretty much always failing) to make the university’s IP portfolio net positive. At your nonprofit, IP decisions are in the hands of the Board, who are legally obligated to uphold the mission of the nonprofit (that you set). If the mission is to “change the world with X technology”, then the Board needs to make the best decision for making that happen. Sometimes that might be licensing technology to a for-profit that can make it scale, other times, it might be to open source the IP. The key is that when the nonprofit is founded you get to write down what the goal is that will drive IP decision making.

In all cases, when IP generated by a nonprofit is licensed it needs to be done at ‘fair market value’. This is an IRS term that is designed to prevent for-profit companies from just separating their entire research arm into a nonprofit, doing research with tax-free dollars, and then giving the results straight back to their for-profit for free. These considerations apply not just to IP but to other things with economic value built with the nonprofit money.

So tldr: yes, you can do research at a nonprofit and then later spin out a for-profit, and the necessary licensing needs to be done at fair market value.

What’s the endgame? Computing runway

That’s it! You now have a functional nonprofit that can employ people and make things happen!

Now you’re in the same boat as every other academic lab and startup company: you have a fixed amount of money in the bank that dictates how long you can operate before you need to fundraise again. It is useful to have a spreadsheet handy to keep track of how much runway you have, and how that number is modified if you choose to hire an additional person.

Different research nonprofits have different visions for the long-term. Some examples:

You might be aiming to execute a project that will be completed in a fixed amount of time and then dissolve (like, say, a political campaign, or a Focused Research Organization).

You might be creating a research nonprofit with the intention of building it out into a research institution that will exist in perpetuity (like the Arc Institute, or the Broad). In this scenario you should have a plan for when you are going to write grants, raise more philanthropic money, and/or raise an endowment before your runway ends.

You might be creating a research nonprofit with the hope of generating for-profit spinouts. In this scenario, pay attention to how you handle IP.

You might decide your nonprofit is destined to have revenue that will sustain its activities in the long run, like iGEM.

It’s a big world out there of nonprofits, and they’re very diverse. Indeed, you probably interact with a lot of institutions that are nonprofits, including:

Infamously, OpenAI

IKEA

Novo Nordisk

SRI, a nonprofit that gets a lot of government funding.

Battelle, which runs many national labs.

The blessing and the curse of research nonprofits is that you get to customize the endgame to your heart’s content. The ultimate goal doesn’t need to be tenure (academia) or profit (industry) - it can be whatever you want it to be (!) If you want to make your own adventure outside of the black-and-white standard options, you need to do the work to articulate what your vision is and communicate it to funders and the people who work with you.

Conclusion

TLDR: it’s pretty straightforward to create your own nonprofit organization. If you’ve ever interacted with a university, you will probably appreciate that doing it yourself might just be less work. 😛 If you have an idea that doesn’t quite fit in an existing box, don’t let the mechanics of getting the organization set up stop you from making it happen.

Contribute to the living doc

Relative to the materials that are available for starting a for-profit or an academic lab, starting a nonprofit research organization is relatively untrodden territory. I’m going to host a living document where folks can send in additional advice or questions.

If you have material you’d like to add, or questions you’d like to incorporate, just email alden.debenedictis[at]gmail.com, message me on twitter @erika_alden_d, or request edit access. Say whether you’d like your additions to be anonymous or not!

The living doc already has lots of good additional info - please do visit if you want to hear more!

Update March 31 2025

If this document was useful to you, check out The Astera Institute’s expanded Nonprofit Guide that walks through every step in much greater detail. A great resource!

Thanks to

Nick Gjokaj, who is an absolute ops wizard and makes it look easy (!!) Tom Kalil, who introduced me to the world of nonprofit research outside of academia, and first explained to me what a ‘fiscal sponsor’ is. Also thanks to Sam Rodriques, Andrew Payne, Yunha Hwang, Ivana Cvijović, Chloe Hsu, Ben Reinhardt, Adam Marblestone, Anastasia Gamick, and Dan Goodwin for questions, comments, and feedback.

Absolutely godsend of inspiration and facts!!! Thank you for creating this. Found you via Grok btw…

As a FRO founder, I *still* found this wonderfully helpful. Thank you for putting this together!